I am Alistair Theodore Morell, a master’s student at the University of Edinburgh, completing my final year project. I was very lucky to be selected for an internship at Voice of Nature (VoNat) in Cameroon, sponsored by Global Diversity Foundation (GDF) to form the basis of my final year written assessment. My Internship at VoNat began in February 2025, when I took the long flight from Barcelona, through Istanbul to Douala, Cameroon. I was very excited and a little nervous about travelling so far to a continent I had never visited before, and I was not so sure what to expect upon my arrival. My nervousness was partly due to the visa process not being very clear, so I was worried that I would not even make it past the border! Luckily, I did everything correctly and made it through passport control, and after a long wait with no internet connection, I collected my luggage. Thankfully, Ndimuh Bertrand Shancho, the Executive Director of VoNat, had managed to get through to the luggage collection area and waved at me from outside. I instantly felt relieved and ready to start the adventure!

Pre-Field Arrangements & Travels

My first couple of days were spent in a hotel in Douala, working with Shancho and some of his colleagues on a plan for our activities out in the field. My focus was to work with VoNat to collect baseline data in the Mount Mbam Area for their initial stage of a 20-year restoration plan that had been envisioned. We gathered various maps on land use and habitat coverage and produced an itinerary to collect data on the ground, and developed a community questionnaire to gather information from the locals on their perceptions of land degradation, land use, and restoration. Within a couple of days, we were ready; before this point it wasn’t 100% clear as to how we would be collecting data on the ground. I had researched a few potential methodologies that we could use. In the end, we opted for using GPS data point collecting when exploring the mountain, to use as validation for the satellite maps, we had collected.

The next step of the expedition was to travel to the Bangourain community, which is situated alongside the southwestern flank of Mount Mbam. The journey was also quite long, first an 8-hour bus journey to Foumbam, a large town near to the mountain where we spent a night before continuing to Bangourain the next day. It was nighttime by the time we arrived at Foumbam, and we were both exhausted from a day of travelling. The next day, to my surprise, 8 people were squeezed into our taxi, with one person sat in between me and the driver! After another hour or so of travelling, we reached Bangourain. The town was bigger than I expected, as from the satellite imagery it looked like a collection of sparsely distributed small buildings. In reality, it is a bustling town full of life; we arrived on Monday which was the day of the weekly market, and motorbikes were zooming around from all directions, with people exploring the market products such as fresh fish, clothing and electronics.

Data Collection & Preliminary Discoveries

The first step of our visit to Bangourain was to introduce ourselves to the Village Chief, who oversees the Bangourain community, including the smaller settlements that surround the mountainside. Shancho had already introduced the project to him, and the chief’s authorisation had been given. We conducted our first community leader interview to understand what challenges the community faces regarding land degradation and how the land is being used. We discovered lots of interesting information about the local wildlife that could be found and some of the key issues that people faced, such as reduced crop yields, drought, poor soil quality, etc.

We continued to interview some other key leaders in the community, including the mayor, who was very receptive to the restoration project. He had studied environmental issues before and was very aware of the issues faced at Mount Mbam and the reasons behind them. We met with the local government official too, the Divisional Officer of Bangourain Subdivision, who was also very interested in the project and wanted to see restorative activities implemented across the landscape. This was very encouraging to see community leaders not only being very aware of the situation but also appreciative of the efforts VoNat was making to help them. This made us feel very welcome, and meant we did not face many challenges to convince community leaders of the need for our research. We were also put in contact with community experts who could assist us with speaking to the various traditional chiefs in the smaller communities nearby and who had knowledge of the mountain.

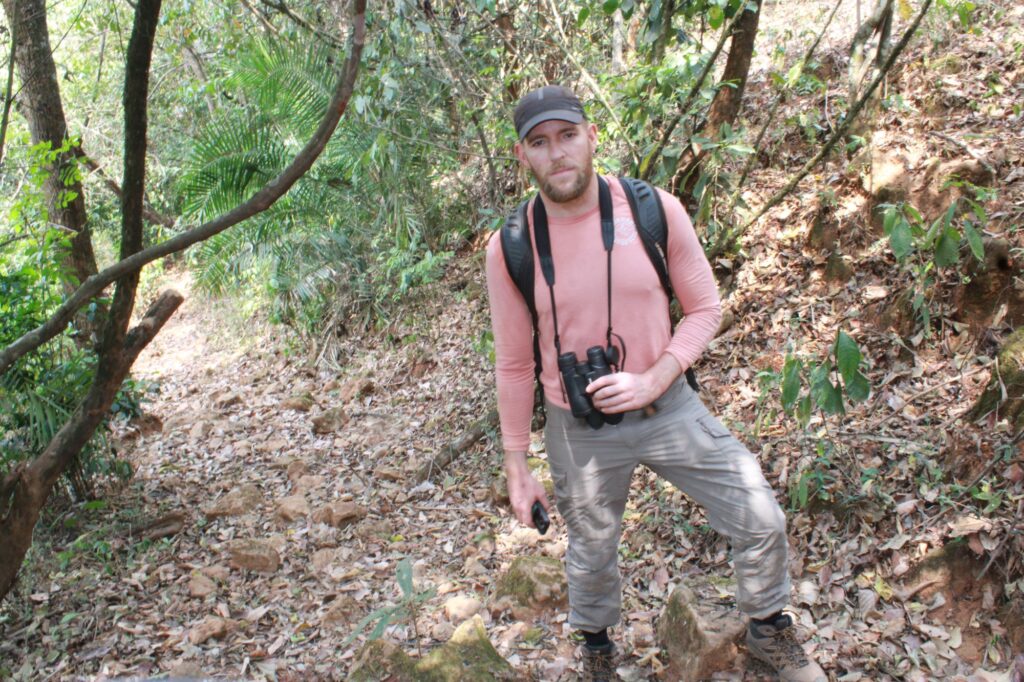

The next few weeks were spent visiting all of the communities that our expert had informed us about, interviewing the traditional leaders, and administering questionnaires to over 60 community members. Every couple of days we visited a different village and would then conduct ground surveys of the mountain nearby. This meant we explored many sections of the mountain, from the most northern point to the southeastern flank. The days climbing the mountain were tough at times, hiking in 34-degree heat, sometimes covering as many as 30,000 steps in a day. It was worth the effort, as we gained a good understanding of land use at varying altitudes and engaged with many of the small herder communities that live on the mountain. It also became clear how modified and degraded the mountain was.

The majority of tree species we observed were not native, whereas bare ground, bush burning, and deforestation were evident everywhere. We struggled to see much biodiversity but did observe some grey monkeys running away in the distance on a couple of occasions. The site is known for its important bird diversity, and it was clear that conservation and restoration are urgently needed to ensure their survival. Only small sections of forest remained, often alongside small streams running down the mountain, which provided an important refuge for the remaining animal species. We were informed that chimpanzees could be found, but they no longer would come near the communities, either due to being less abundant or avoiding human settlements for fear of being hunted.

Conservation Education Experience

We also concluded that education and awareness of the importance of conservation are needed. People often hunt bushmeat indiscriminately, not necessarily realising the adverse impact this is having on wildlife. On two of the days, we visited local schools to give a session on biodiversity conservation, and I was surprised to see how little awareness there was of the species that can be found around Mount Mbam, and the risk of them being made locally extinct.

Shancho delivered an energetic and inspiring session to the local high school, which engaged the students. I even had the opportunity to teach to the students, but I fear they struggled to understand my British/ Birmingham accent, which was evident from their perplexed faces at times.

Community Engagement in Mapping Restoration Sites & Options

Once we had collected all of the questionnaire dates and had explored the mountain, I analysed the results to summarise the key findings. I created maps from the GPS points we collected to demonstrate the scale of the problem we had found from bush burning and land degradation. A workshop was then planned, where over 50 community leaders attended to be briefed on our preliminary findings. This was a great opportunity for me, where I created and presented a PowerPoint on our findings. I discussed the main issues we had been informed about, including fertiliser and chemical overuse, reduced yields, bush burning and longer droughts. I also summarised some key opportunities that had been identified. The vast majority of participants were in favour of restorative action, including the restoration of farmlands and reforestation. I researched some regenerative farming techniques that had been proven successful in other African counties to improve soil quality and increase yields without the need for chemical inputs. Women attended the meeting and were keen to understand how they could reduce their impact on tree biodiversity by only harvesting firewood from trees that were not threatened or important for biodiversity. At the end of the workshop, people worked in groups according to which village they lived in, to devise some initial land use plans for their communities. These outlined areas for reforestation, regenerative agriculture and agroforestry land for grazing livestock.

All in all, the trip was an eye-opening experience and something I will never forget. I met incredible people who were trying to improve the livelihoods of local people and protect the environment. The passion, and willingness to participate in the restoration project was heart-warming, and I see there is a real opportunity here to work with the community and make some amazing improvements. I am hopeful to continue to support the project in the future and see some of the changes implemented for the benefit of the people who live in Bangourain and to protect the landscape for its biodiversity and natural beaty.